Content note: rape; rape humour.

As happens all too often (sigh), I’ve decided to weigh in on a topic that I’d planned to leave to the other thousands of feminists out there on the internet: namely, the Daniel Tosh rape joke debate. I may be late to the blog party, but I’m fairly convinced I can still add something of value to the discussion.

Daniel Tosh, he of Tosh.0 fame, is an American comedian and “professional sayer of stupid shit” who caused a massice media hoo-ha a couple of weeks ago by telling his audience that it would be hilarious if a female heckler who objected to his particular brand of rape-joke humour was gang raped. The below is from a blog entry written by the woman in question, describing Tosh’s response to her heckle that “rape jokes are never funny”:

After I called out to him, Tosh paused for a moment. Then, he says, “Wouldn’t it be funny if that girl got raped by like, 5 guys right now? Like right now? What if a bunch of guys just raped her…”

The response was predictably divided: feminists and the unfunny damning the statement braced glaringly on one side, and staunch pro-freedom of speech activists and liberally-minded comedians on the other. At least, that’s how some respondents have outlined the scenario. As ever, the response has been branded an overreaction by women of a certain delicate disposition. Criticism of Tosh and his maverick merry-making shenanigans has been called an attempt to quash free speech and impose strict limitations on the material available to comedians.

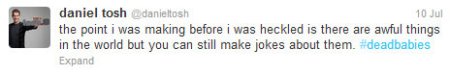

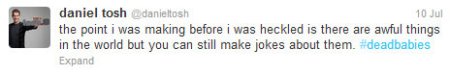

My attitude isn’t pro-censorship; I don’t think that comedy should necessarily be limited to topics which carry no risk of offending someone. Tosh actually made a similar point in a tweet after the event:

Yes, you can, Tosh. But that doesn’t mean you should.

While the argument that no topic should be exempt from ridicule is valid, it’s a lazy and essentially irrelevant defence in this case. Intelligent comedy often derives some of its value from its power to address controversial subjects. A comedian who can make an audience wince with a well-penned one-liner can also make them think. This is what separates the cruel from the insightful.

I don’t tend to enjoy most jokes about cancer, HIV, infant death and similarly upsetting tragedies, but I can’t help feeling that discussing them in the same breath as jokes about sexual abuse is misguided and unhelpful. Here are three reasons why:

#1: lack of comedic value

For a good comedian, a heckler, while irritating, can be a fantastic opportunity to show just how quick they can be. Their retorts can become highlights of the show. So for Tosh, the interjection was a chance to demonstrate his razor wit and improv skills.

Tosh’s statement was categorically not funny. It had no intrinsic or contextual comedic value: no element of irony, satire, wry social comedy or even plain old slapstick. Because of this, it seems putting down the heckler came before entertaining the audience.

#2: prevalence of rape

This part of the argument is almost painfully simple to understand. A hostile reaction to a casual reference to rape is often dismissed as over-sensitivity on the part of the listener.

For starters, I would argue that to take offence is a perfectly justified reaction in this particular scenario. Tosh’s comment was mean-spirited and misogynistic even before we arrive at the complexities behind the debate. But for many people, a hostile reaction isn’t one of offence, but a very real and powerful pain.

Rape statistics are difficult to pin down, as a high proportion go unreported, and of those that are, many don’t progress to prosecution. According to the Colorado Coalition Against Sexual Assault, in 1998 an estimated one in every six women in America had experienced an attempted or completed rape; some bodies suggest that the current figures are much higher. An estimated 60% of rapes go unreported – this figure rises to 95% among college students, who make up a not-inconsiderable proportion of Tosh’s target demographic.

These alarmingly high figures demonstrate that the likelihood of encountering people on a day-to-day basis who have suffered a sexual attack is high. In any given group, there’s no way of knowing whether anyone has a history of sexual abuse. Because of this, I tend to operate on the principle that it’s better to avoid flippant references to a topics that might unwittingly cause considerable harm to anyone present. Simply put, there’s very little personal sacrifice involved in not making rape jokes. Weighed against the considerable emotional pain an ill-timed comment could inflict, this tiny effort seems to me to be a no-brainer.

In the context of the Daniel Tosh debate, statistically, there’s a high probability that one or more members of his audience will have been the victim of sexual abuse at some point in their lives.

Rape humour, except in the very rare cases when it is handled with great dexterity, is a brand that exploits people’s pain for laughs. That’s a pretty shitty thing to do.

Culture Map Austin published a response from a comedian called Curtis Luciani, who tries to persuade a male audience of the serious implications of using rape as the subject of humour, and why it must be tackled with great skill. Its refreshing to read a frank and eloquent (if you think it’s crude, stick with it) male response which attempts to build a kind of empathy with the pain and humiliation suffered by sexual abuse victims when rape is handled insensitively:

People have wounds, and those wounds are painful. That doesn’t have shit to do with the weak concept of “taking offense.” If someone talks about Texas being a shitty state, I might “take offense” at that. Fine, whatever. All of us who like comedy are generally in agreement with the idea that “taking offense” is lame, and a comedian should be willing to “offend” whenever he or she wants to.

But causing pain is quite a different fucking matter. Your job as a comedian is to take us through pain, transcend pain, transform pain. And if you don’t get that, you are a fucking bully, and I’ve got zero time for bullies.

#3: rape as a source of shame and humiliation

Tosh’s intention was to humiliate his heckler by making the audience laugh at the idea of them suffering in a particularly violent manner. And it sounds like he succeeded:

I should probably add that having to basically flee while Tosh was enthusing about how hilarious it would be if I was gang-raped in that small, claustrophic room was pretty viscerally terrifying and threatening all the same, even if the actual scenario was unlikely to take place. The suggestion of it is violent enough and was meant to put me in my place.

Tosh achieved his aim of subduing his attacker by creating a hostile environment in which to humiliate and shame her.

You know what else is used as a tool to shame and subdue women? Rape. It robs the victim of dignity, power, and self-esteem. It’s a weapon used to overpower and humiliate women (and men), to force them into submission. This is what differentiates sexual abuse from other controversial topics. There’s an element of not only victimhood but victimisation which is absent from narratives of disease or other ill-fortune. It entails intended and deliberate harm, whose psychological consequences are overwhelming and incalculable – to the extent that women are ashamed to admit to something about which there is no earthly reason why they should feel ashamed.

Rape culture is propped up by wide and indiscriminate ‘slut shaming’ everywhere – from the criticism of under-dressed clubbers to judgemental tabloid columns. The whole victim-blaming narrative hinges on the fact that blame is often apportioned, at least in part, to the victim of sexual attack. Just look at the Twitter furore surrounding the Ched Evans rape case.

It’s because of this that it’s particularly important to handle the subject of rape with a great deal of sensitivity. When much of the discussion surrounding a subject is already incredibly damaging, comedians, if they opt to wade into such territory, must aim to challenge and not to enforce these narratives.

In the face of all this, ‘free speech’ seems a pretty weak defence – and a self-defeating one at that. Using violence, the threat of violence or even flippant references to the same to silence criticism is an attempt to deny them an opinion or a response. Surely that is a greater attack on freedom of speech than criticising someone’s comedy? Any attempt to reverse the roles of victim and oppressor to paint Tosh as the marginalised party falls rather flat. I don’t buy the idea that comedians are exempt from all social convention and accountability. They, like anyone else, must consider the impact of their words. Because otherwise, Curtis Luciani is right. You are a bully. And there’s not much that’s funny about that.

Image: redfriday on Flickr